I Wanna Be Your Carrie Brownstein

The first, last, and only time I talked to Carrie Brownstein on the phone was in 2011, and I was having an existential crisis.

She didn’t know because I was a Seattle Times journalist interviewing her and, frankly, it would have been pretty weird if I had just started in on how I had built a whole career talking about other people’s art and shoving mine under the floorboards but how now my own need to create, be seen, and be heard as an artist in my own right was tearing the house apart from the inside out.

Instead, we talked about Carrie’s Portlandia live show— a sort of concert variety show coming to Seattle in conjunction with her and Fred Armisen’s TV show, Portlandia. Carrie was very nice, and I remember feeling surprised that she wasn’t more aloof or taciturn as so many rock stars often were during interviews. She was warm, funny, self-effacing. I didn’t ask her about her band, Sleater-Kinney, because, at the time, they were still broken up and wouldn’t reunite publicly for another three years. (The interview is here, published under my given last name, which I swapped out for another family name when I started performing country music in Texas. I didn’t realize it at the time, but the article would be the last one I would write for the Times, or for anyone as a journalist).

Today, in 2025, I just finished listening to the audio version of Carrie’s 2015 memoir, Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl. I cried as she read the final chapter and then the epilogue, wiping away the tears as I pulled into the parking lot in my Pasadena apartment. Then I came inside to write this love letter.

The funny thing, though, is this is a love letter both to Carrie and to myself. The deep and specific appreciation of a piece of art that so beautifully spills free the artist’s story and also somehow has room for me. Even though the book is nearly a decade old now, it came to me at the right time, which is the magic of inspiration.

This is a love letter to an artist who feels within reach, meaning she is skilled in the art of relatability, something I aspire to as well. We’re all just hanging out, drinking coffee, and having an existential crisis together. And that was a hallmark of the riot grrrl scene she was a part of in the 1990s in Seattle and Olympia– women, girls, making music for each other because there was something important to say.

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah

I wanna be your Joey Ramone

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah

Pictures of me on your bedroom door

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah

Invite you back after the show

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah

I'm the queen of rock and roll

-Sleater-Kinney, “I Wanna Be Your Joey Ramone, 1996

Substack feels like an echo of that time, just less feral, less unboxed, less unfiltered rage. I’m still figuring out how to put my body into the screen and what to say when I get here. I’d prefer we all gather in a basement and howl.

I read Carrie’s book on the recommendation of my friend Katie because I’ve been writing a play about a group of women in their 40s who were in a high school punk band together. The punk band was a short-lived endeavor, but it imbued them all with an imprint of what it is to be able to channel all of your rage into something that can be witnessed and even applauded. As adults, they’re angry at the ways their lives have failed them (or vice versa) but have no outlet. To grow up, we usually believe, is to get quieter and more sensible. One of the characters, supremely pissed off at a situation with her boss, gets them all back together to try to shock alive the nerve of high school bravery and expression.

The play is a commission from Chance Theater, which is a lovely small theater in Southern California with a really generous new play development program. As I’ve been writing, I keep worrying I’m writing something too wild and angry for their more conservative audiences. I shrink back, try to make the play easier to understand, more safe.

This writing experience mirrors a larger existential crisis around what it means to choose to make art (and if you can even choose at all– perhaps it is just demanded of you), which I talked about in my last Substack post. So, yet again, Carrie Brownstein is with me, unknowingly, as I ask: “Where does my voice belong? Where is it needed?”

I listened to the audiobook of Hunger Makes me a Modern Girl over the last four days as I’ve re-written the play entirely. The second draft was due last week, but I begged for an extension. The book reawakened chapters of myself long dusty, as well as mirrored a new, larger fire to say the quiet thing out loud (hence this article I wrote about leaving Meow Wolf).

I’m left with an impression of Carrie (I feel compelled to use her first name because, you know, this is a love letter), as someone so self aware that she is compelled to turn her skin inside out and show it to the neighbors: I know I’m full of blood and guts and shit. Have a look.

In her book, she pulls out the innards of a life driven by creating, in all its messy motivations: art to be seen, art to be liked, art to be adored, art to process and grieve and scream. The book clawed into me so deeply that now all I can do is write in response. Not quite a review, but something that is maybe art in exchange for art. I stubbornly now insist on putting myself in my writing, for better or worse.

When I used to write concert reviews and previews for the Seattle Times, I often wrote about artists I didn’t know well, was not already a fan of. The Times covered big pop, rock, and country acts. Before that, I spent nearly six years as a DJ for my small town college radio station in Ellensburg, Washington, about two hours east of Seattle, a town and a radio station not known for “big acts.” I started DJing while I was still in high school because my dad had a world music show on the station (at the time very embarrassing to me), but he got me hooked up to take shifts that college students didn’t typically want (i.e Saturday mornings). The year I graduated from high school, Sleater-Kinner released All Hands on the Bad One, and I played the title track every shift.

My sophomore year in college, at the same college in the same small town, I became music director of the station. Most of the DJs were guys who wanted to play rock and metal. I liked weird indie pop, garage rock, and girl punk. I programmed what I liked into the rotation, and the DJs complained, but I was the one listening to all of the CDs being shipped in each week, spending hours talking to label reps who thought flirting with me would get their bands played (sometimes it worked). I played so much of the up-and-coming band The White Stripes that the label hooked me up with free tickets to see them at the Capitol Theater in Olympia in 2002, still one of my most bragged about musical experiences.

In college, I tried to be both an arbiter of art and an artist. I was the music director, and I also played in an earnest, feminist folk duo with my friend Leah. Leah loved the Indigo Girls, Ani DiFranco; I just wanted to perform. I wanted to be seen and admired as “the next big thing” because my panic disorder had kept me from leaving the small town. I tried: I got accepted to a college three hours away, but after packing all my stuff and then unpacking it in the dorm, I was too terrified to stay. Back in Ellensburg, ashamed and depressed, I tried to construct some identity for myself that was going somewhere, even if I was not.

In high school, punk had become a small, sonic rebellion when I was too afraid to take bigger risks. Panic disorder kept me small and scared to drive to Seattle for shows, though I would obsessively scour the Rocket, Seattle’s music alt-weekly when my parents and I would drive over once a month to go grocery shopping at the natural foods store. I would imagine answering an ad, joining a band.

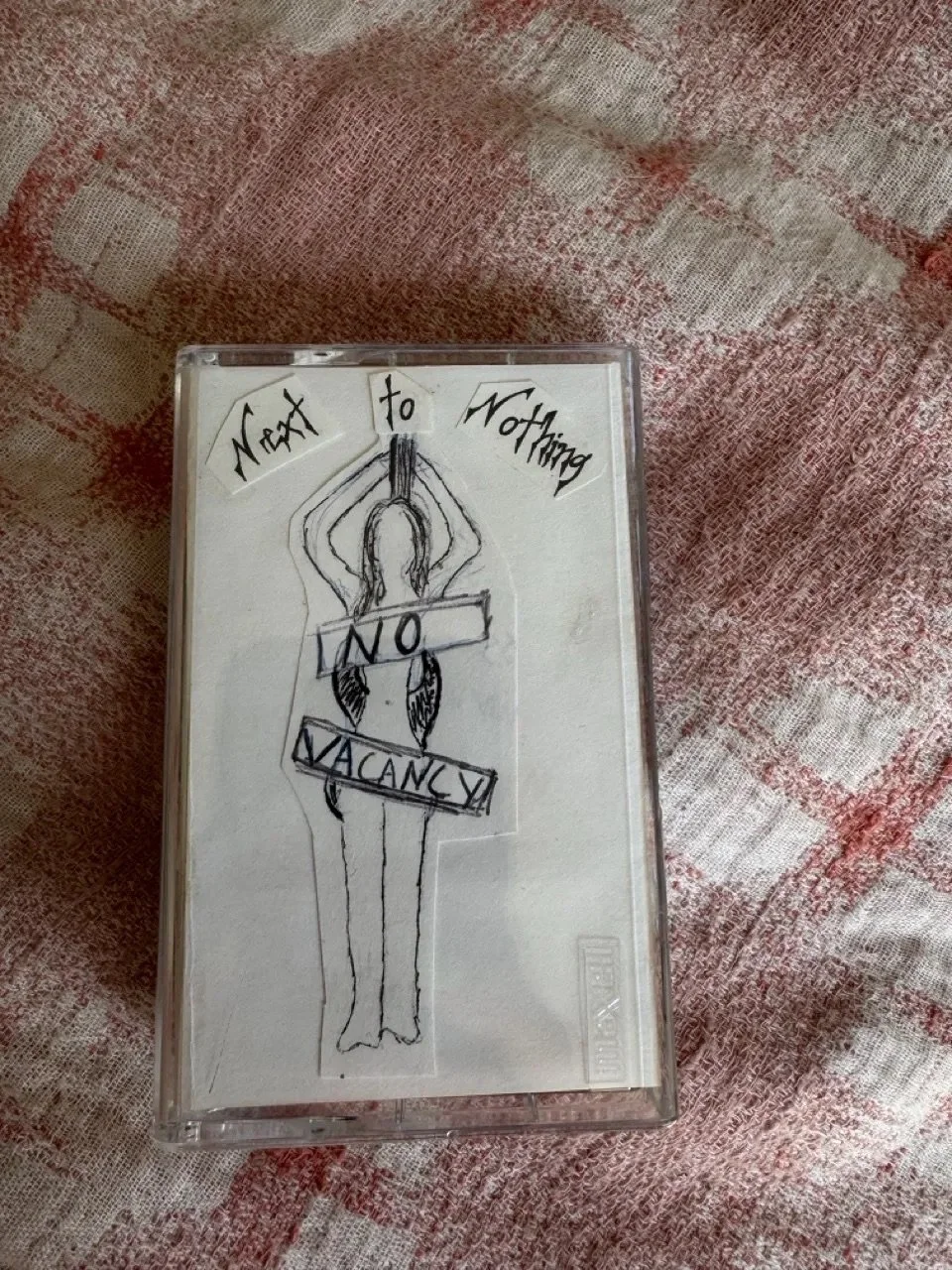

My senior year in high school I started a punk band with two guy friends. I wanted an all-girl band but I didn’t actually have female friends who wanted to play punk music, and I didn’t know enough to rally and teach them. Tom (whose name I insisted on spelling Thom because of Thom Yorke— sorry, Tom) and Dave and I practiced in Dave’s driveway out in the country to an audience of two barking dogs and three chickens. We recorded a demo at our friend’s house with no drummer (see the explanation in the demo tape lol). We never played a show live, but just being in a band was thrilling. We belonged to something. We had something to say, and we were figuring out how to say it.

Like many things I did in high school, the band was me playing at rebellion, though I couldn’t really say what I was rebelling against. The things I more subconsciously knew to be painful— being one of only a handful of Jews in a small rural town where kids made anti semitic comments straight to my face in the hallways; being the daughter of a mother with severe PTSD— I didn’t yet have awareness or language around to make art out of. The best I could do I rebel through affect, Doc Marten knee-high boots, the dog’s choke chain I turned into a necklace, a mixed tape I called “Fuck You” that had the loudest, angriest songs I could find and would blare from my Toyota Tercel with the windows rolled down defiantly. Just try to get me to turn down the volume!

In high school, my musical taste was initially shaped by my freshman year boyfriend, Patrick, who kissed me in his bedroom while playing a Radiohead b-side EP, shoving his wallet chain out of the way so we could sit together on his twin bed. Radiohead quickly became my favorite band, surpassing Patrick’s love and knowledge. I spent countless hours at the town’s bastion of coolness, Rodeo Records, looking for rare Radiohead releases.

But Pat’s best friend, Joey, played in a punk band, so we would go down to the Hal Holmes Community Center to watch them play Misfits covers. I was horrified and fascinated by the violence in the lyrics and the casualness by which they were delivered and also the undercurrent of rage in the room, a room filled with young men slamming their bodies against each other like they could push their skeletons free.

I was jealous of their freedom– freedom from the fear of losing control of their bodies, the fear that plagued me and kept me small. I took their music and made it my anthem to wildness: the Dead Kennedys, the Sex Pistols, the Offspring, Nirvana. These boys didn’t listen to women singers. I found the women through the radio station: Sleater-Kinney, Bikini Kill, Hole.

And then, when I was in college, a band of thirteen-year-old punk girls calling themselves Savage Lucy popped up right in my hometown, and they were surprisingly excellent, everything I aspired to be as a teenager. I wrote an article about them, and, with the help of a college mentor, pitched the story, which became my first Seattle Times byline, which I parlayed into an internship and then a long stint of regular freelance work.

When the Seattle Times wanted me to cover Brooks and Dunn or Dave Matthews Band or Fergie or Janet Jackson or Keith Urban, I had little knowledge to stand on. All I knew was that a lot of people liked these artists. And so I would try to, as quickly as possible, fall in love. I felt like it was my duty to understand why they were so popular and then to review the show through the eyes of the fans, not my own often-pretentious obsession with obscure up-and-comers.

As I was writing for the paper and working a full-time job as the Communications Manager for a large regional theater, I was also trying to be a musician and an actor on the side. I wasn’t failing miserably, but it was a struggle. In 2011, the year I interviewed Carrie, I performed the country music play I wrote at Bumbershoot with Mark Pickerel (formerly of the Screaming Trees) as the drummer. Our Ellensburg connection had opened the door to this unlikely, pinch-me performance, but it was fraught with anxiety. I wanted so desperately to be liked by the audience; I didn’t yet understand, even after all that punk music of my youth, it wasn’t about being liked. It was about transmitting a feeling, an experience.

Mark invited me to open for him for a few dates in Eastern Washington near where we had both grown up. I played one show, but it brought on such intense fear that I canceled the second, telling Mark I’d come down, over night, with some illness.

Carrie’s account in her book of touring with Sleater-Kinney with stress-induced injuries, anxiety, and depression, made me feel as if I’d climbed into her body. I knew for certain that, yes, that’s what would have happened to me, too, if I had reached that level of performing and touring. Body and nervous system too fragile, particularly in my younger years when I didn’t understand how to listen to my body until it started fully screaming.

Carrie’s book brought me back to that younger place in myself, the place where I hid behind writing about other’s people’s art because it was safer. Sure, sometimes readers were mad at me for pointing out a singer’s flaws or getting a fact wrong, but that was easy to swallow. The harder thing to do is make the art. And then to keep making the art again and again in different configurations, circling the drain of truth.

I wrote lyrics for the punk play (titled, for now, Punk AF). There will be music, too, eventually, but for now I have a lyrical sketch of what the characters are feeling. To write the lyrics, I opened the channel, the one to the place where we bring through inspiration from The Muse. But I opened another channel, too, one to the younger part of myself, yearning to be heard and seen, the one with wisdom I haven’t always listened to. Or maybe the two channels are actually the same.

These are the lyrics to the final song in the play, where the women realize that, yeah, maybe no one cares to hear them sing, but they’re going to, anyway.

We’re gonna start slow

We’re gonna start slow

Gonna go back

Gonna go back

The way things were

Just a panic attack

Shake the tornado

Shake the tornado

Love on the run

Love on the run

We grew up sideways

Spit out the gum

We get through one little road home

We get through one little road home

We get through with a new kind of gun

We get through with a new kind of gun

Say the quiet part loud

And loud is hush

What a rush

What a rush

To be here all again

Say the quiet part loud

Take a breath, no rush

What a love

What a love

To be here at the end